Essays

Show

How True is Art History?

‘A Female Sisterhood?’

‘Who Owns The Nude?’

Raphael Mazzucco: Barely There

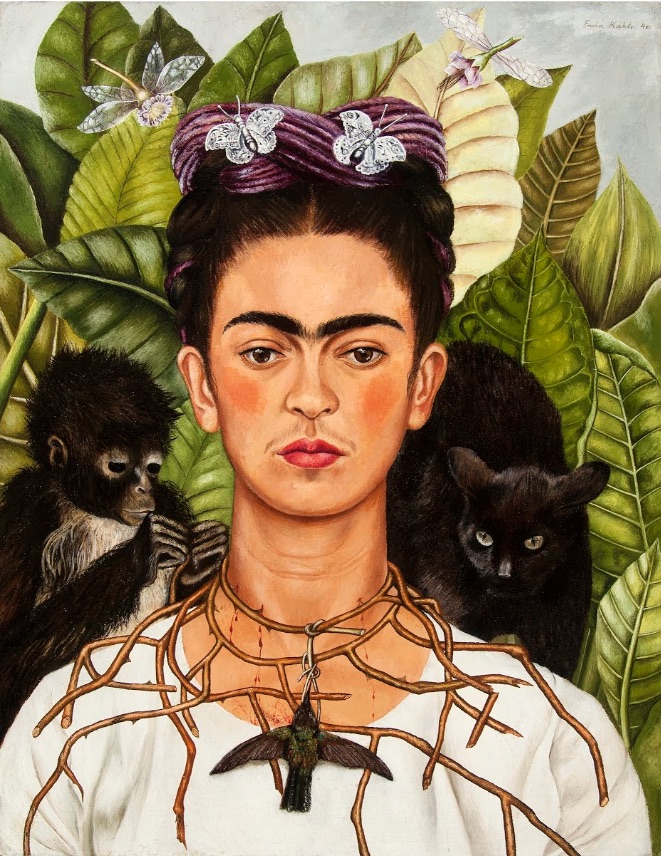

Why We Need To See Frida Kahlo Beyond Her Biography

With the rise of Frida Kahlo’s fame and fandom, especially since her death in 1954, it’s easy for different versions of the artist to be created. Since she started out, her identity has been blurred and influenced by the biographical details of her life, for instance, her success constantly being measured against her husband Diego Rivera, or her work being dismissed as Mexican folk art because of where she was from. While these elements of Kahlo’s life are of course important to consider when looking at her work, they only provide a surface level understanding of the complexities that resided within her mind. To get a better understanding of the artist beyond the factual details of her life, we spoke to author Frances Borzello. In 2016, Frances wrote Seeing Ourselves: Women’s Self-Portraits, a diverse exploration of female artists and self-portraits from the 12th century to modern day. Frances also co-wrote

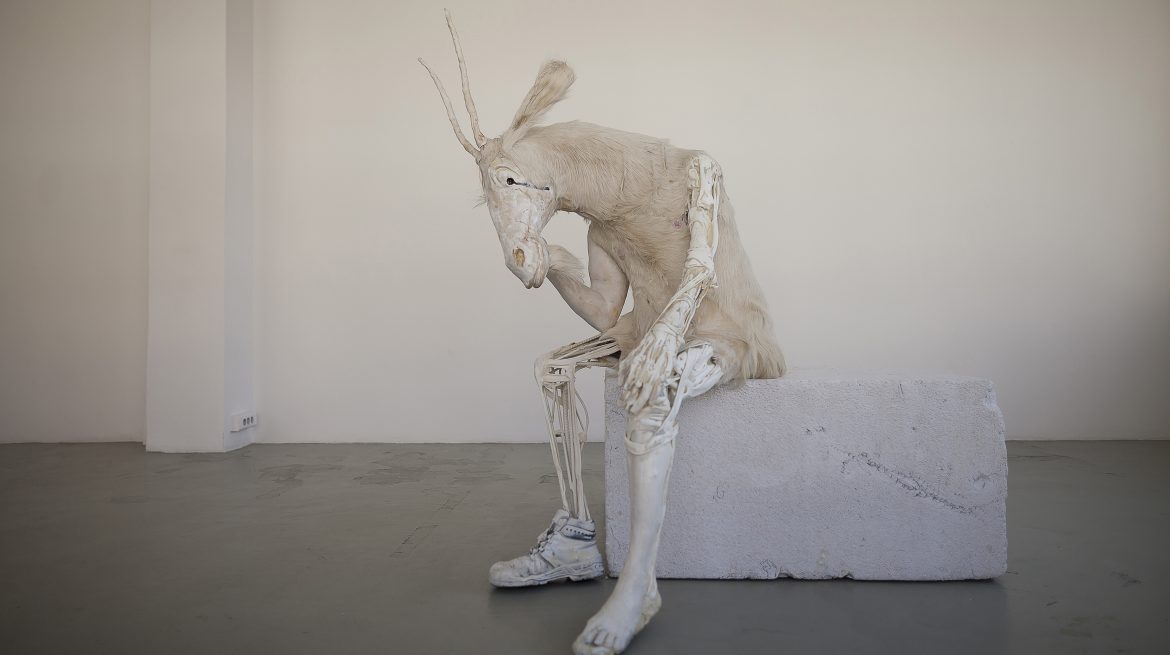

Self Portrait as the Billy Goat: Mirror Image

Once upon a time, everyone knew what a self portraits was: an artist’s painting of his or her own face . In earlier centuries, they made them for a patron, for experimentation , for reproduction as a print, or as a way for prospective clients to assess the artist’s skill by comparing the real with the painted self portrait. Search engines still accept this definition. Type in how to paint a self portrait and you will be overwhelmed with advice involving mirrors, the placement of facial features and hints at how to trap a likeness. And yet when you look around this exhibition, this definition crumbles. Even the images that look traditional are not what they seem on the surface. Andre Breton’s self portrait was made by an automatic photography machine in 1924 and Linder’s image was taken by the photographer Christine Birrer in 1981. In both these cases, the

Life Drawing and the Male Model

We all hold an image of a life class in our heads: a naked human holding a pose in front of a group of clothed students silently transposing what they see into pencil, paint or charcoal. Jeremy Deller calls the lifeclass the bedrock of art and art history. “The life class is a special place in which to scrutinize the human form. As the bedrock of art education and art history, it is still the best way to understand the body’. But what does bedrock actually mean? To most people, mastery of the nude proves the artist’s ability to draw properly, ‘properly’ meaning in a realistic manner. And that is certainly part of it. But the life class has a bigger history, one yoked as tightly to the history of post Renaissance western art as the hand that holds the pencil. Authority for the life class can be traced back

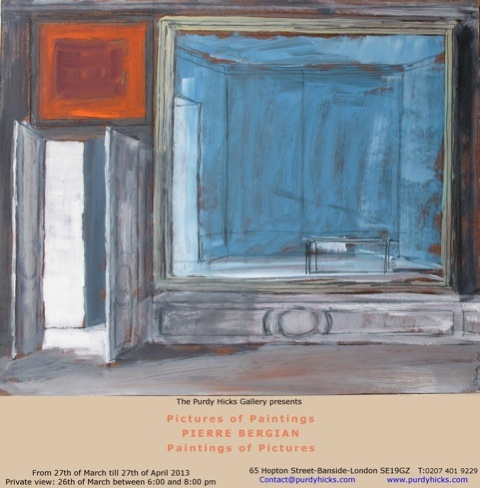

Pierre Bergian Paints Empty Rooms

Pierre Bergian paints empty rooms. Well, not completely empty. Sometimes there is a solitary piece of furniture, a ladder, a piano, a table, but these seem to do little more than add to the emptiness. ‘My paintings are a little similar to still lives,’ he says.’Emptiness fascinates me.’ Or perhaps peace would be a better word to describe what this Belgian artist creates on canvas. Lacking a chair and a musical score, the only notes the piano suggests are yet to be played or belong to the past, facts which add to the silence rather than filling it. Empty they may be, but they are full of atmosphere. ‘My paintings are simply poetic; I am not interested in any conceptual meaning.’ They are also full of light. ‘Being interested in light is not exceptional for a painter. But I never paint artificial light. I love sunshine coming into a room

Body of Knowledge

As you step off the escalator on the fifth floor of Tate Modern, you come face to face with a time line of twentieth century art. And there, written high on the wall under the heading Feminism, is the name Judy Chicago, one of a select group of five women the Tate sees as responsible for art’s swerve into previously untravelled territory. The most famous of the works that earned her that writing on the wall is The Dinner Party, 1979 , a huge triangular installation 48 feet long on each side with 39 place settings celebrating 39 noted women and with a further 999 names inscribed on the porcelain floor providing a historic context for the women represented at the table. Sitting at home in Islington in 1980, I received an excited phone call from my husband in San Francisco reporting that an extraordinarily long queue was waiting to

Behind the Image

The Art of Ageing

Spent the Day

Uncanny Truths